It may be that many are ignorant of the situation of many of my brethren within the limits of New England. Now I ask if degradation has not been heaped long enough upon the Indians? And if so, can there not be a compromise is it right to hold and promote prejudices? If not, why not put them all away? I mean here amongst those who are civilized. Having a desire to place a few things before my fellow creatures who are travelling with me to the grave, and to that God who is the maker and preserver both of the white man and the Indian, whose abilities are the same, and who are to be judged by one God, who will show no favor to outward appearances, but will judge righteousness. An Indian’s Looking-Glass for the White Man (1833) It joins a line of protest that eventually lead to civil rights writers like Henry David Thoreau and to Abolitionist writers like Frederick Douglass. His text, An Indian’s Looking-Glass for the White Man, insists that whites look at their racial prejudice and mistreatment of people of color, especially Native Americans. With Apess’ help, the Mashpee petitioned the state government, declaring their refusal to allow any whites to “come upon our plantation, to cut or carry off wood, or hay, or any other article without our permission.” They claimed their right to self-governance, as they possessed the constitutional rights of freedom and equality.īesides his autobiography, Apess wrote sermons, conversion narratives, and political commentaries. Preaching across the state of Massachusetts, Apess became involved in the ultimately successful Mashpee Revolt of 1833 against the state government, with the Mashpee protesting their being treated as wards of the state. He certainly resented the prevalent mistreatment of Native Americans by whites, lamenting their unjust laws and lack of Christian fellowship. According to his autobiography, he encountered barriers placed between himself, as a Native American, and the church hierarchy, only later being ordained as a Methodist minister.

#A SON OF THE FOREST WILLIAM APESS LICENSE#

After obtaining a license to “exhort” at church services, he became an itinerant preacher. Apess came to appreciate the egalitarian views of evangelical Methodism being particularly drawn to the enthusiasm of their camp revivals and services, he chose to be baptized a Methodist. From 1816 to 1818, he lived once more among the Pequots. He was also introduced to Christianity during this time.ĭuring the War of 1812, Apess joined the American militia and participated in the American attack on Montreal. The family to which he was indentured sent him to school in the winters his schooling lasted six years. At the age of five, Apess was indentured as a laborer. He attributed their abuse in good part to the whites who introduced alcohol to Native Americans. His autobiography describes his childhood as painful, as he was left to the care of poor, alcoholic, and physically-abusive grandparents. Apess was born in Colrain, Massachusetts.

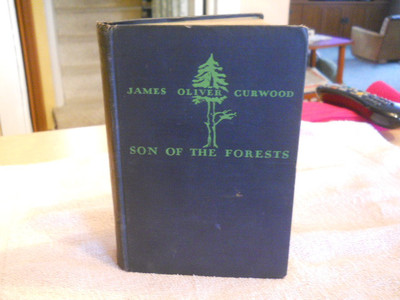

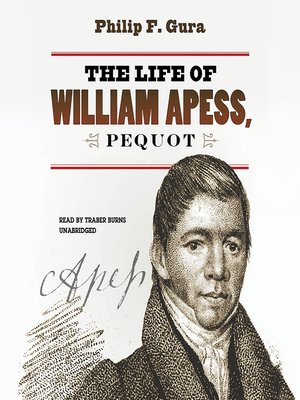

It is possible that Apess was indeed a descendent of Metacom he may also have descended from the Pequot tribe, a tribe that Apess’s father joined. His mother may have been part African American. In it, he writes that his father was a white man and his mother was the granddaughter of Metacom, or King Philip (instigator of King Philips War of 1676). Following Apess from his early life through the development of his political radicalism to his tragic early death and enduring legacy, this much-needed biography showcases the accomplishments of an extraordinary Native American.William Apess is credited as the first Native American to publish an extensive autobiography, A Son of the Forest (1829). Placing Apess's activism on behalf of Native American people in the context of the era's rising tide of abolitionism, Gura argues that this founding figure of Native intellectual history deserves greater recognition in the pantheon of antebellum reformers.

His 1829 autobiography, A Son of the Forest, stands as the first published by a Native American writer. After an impoverished childhood marked by abuse, Apess soldiered with American troops during the War of 1812, converted to Methodism, and rose to fame as a lecturer who lifted a powerful voice of protest against the plight of Native Americans in New England and beyond. Gura offers the first book-length chronicle of Apess's fascinating and consequential life. The Pequot Indian intellectual, author, and itinerant preacher William Apess (1798–1839) was one the most important voices of the nineteenth century.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)